Ancient Greece was a civilization that lasted from the Greek Dark Ages in the 12th-9th centuries BC until AD 600 when the Early Middle Ages began. Three centuries after the crash of the Late Bronze Age of Mycenaean Greece, cities began to grow around the 8th century BC. This was followed by Early Greece and the conquest of Alexander the Great, which brought the Hellenistic period.

- Early Cycladic Civilization: the Early Bronze Age 3200-2000 BC

- The Helladic Civilization: Bronze Age Greece 3000-1050 BC

- The Minoan Civilization: Bronze Age Crete 3000-1100 BC

- Minoan Religion

- The end of the Greek Bronze Age: 1200-1050 BC

- Mycenaean Palaces: Centres of Power and Commerce

- The Geometric Period: beginning of the Iron Age 1050-700 BC

- Early Greece: 1100-700 BC

- The Orientalizing Style: about 700-550 BC

- Greek Daily Life

- Alexander the Great (336-323 BC) and the Hellenistic Age

- The Hellenistic Age: 323-31 BC

During the Bronze age, a succession of local developments took place in the Cycladic Islands, Crete and mainland Greece. There were 3 cultures that emerged. They were related but still very distinguishable:

- The Cycladic culture in the Cyclades

- The Minoan culture on the island of Crete

- The Helladic culture, featuring the city-states of the Mycenaean era.

The Bronze Age was followed by the Geometric Period, which was defined by its art and also marked the beginning of “Early Greece”.

Early Cycladic Civilization: the Early Bronze Age 3200-2000 BC

The Cyclades are a group of islands in the southwestern Aegean Sea, where a distinctive Bronze Age civilization emerged, referred to as the Cycladic Civilization. The earliest settlements were self-sufficient farming and fishing hamlets. Overseas contacts and trade were sporadic in this initial phase.

The next phase saw rapid development and prosperity. Trade flourished as the population centres exported their natural resources, such as copper, silver, emery, obsidian and marble, to Minoan Crete, Helladic Greece and Anatolia. Local manufacturing expanded to include the making of stone tools, pottery, metal objects and ships.

The end of the Third millennium BC was a period of unrest for the people of the Cyclades, but growth, urbanization, and trade continued. A number of centres, including Akrotiri in Santorini, developed into thriving harbour towns.

The Helladic Civilization: Bronze Age Greece 3000-1050 BC

Greeks refer to their country as Hellas and archaeologists use the word “Helladic” to describe the civilization that flourished there during the Bronze Age.

The Early Helladic period, with its many prosperous farming settlements, ended with the arrival of the invaders around 1900 BC. Known later as the Mycenaeans, these newcomers brough advanced techniques in pottery, metallurgy, and architecture, as well as the Greek language.

The Mycenaeans are named after Mycenae, the principal citadel of their confederation in Greece. Along with other strongholds such as Pylos, Thebes and Athens, this fortified palace is immortalized by Homer’s poems The Iliad and The Odyssey. The Mycenaeans dominated Greece and the Aegean militarily and economically from 1400 to 1200 BC. Their contacts with Minoan Crete stimulated the growth of art and culture on mainland Greece.

The Minoan Civilization: Bronze Age Crete 3000-1100 BC

The Bronze Age civilization that flourished on Crete was named after the island’s mythical king, Minos. Beginning around 2600 BC, an early Minoan culture emerged with advanced farming methods and expertise in metallurgy. Minoan demand for copper, tin and precious metals led to the growth of an impressive maritime fleet.

Around 1900 BC, the first large palaces were built. Knossos Palace was the most important. Each had a king who served as theocratic ruler, claiming divine sanction. These palaces were destroyed in 1500 BC by the large earthquake that erupted in Santorini and went as far as Crete, and shaped Santorini the way it is today. The earthquake ended the Minoan Civilization.

The only palace that survived was Knossos, and continued to prosper until its final destruction around 1375 BC. The palace of power in the Aegean then shifted from Crete to mainland Greece.

Minoan Religion

The Minoans worshipped in sacred caves, in sanctuaries on mountain peaks, and in towns. They also used domestic shrines in palaces, villas and houses. Their religious rights involved animal and bloodless sacrifices, votive offerings given in fulfilment of vows, processions, music, dance and prayer. These ceremonies ensured divine assistance for human and animal fertility and favourable agricultural production.

There were two common religious symbols. One of them was the “Double Axe”, which was a symbol of sacrifice and supernatural power. The other one was the “Horns of Consecration”, which were stylized bulls’ horns to mark a place of worship.

The end of the Greek Bronze Age: 1200-1050 BC

Many of the Mycenaean palaces were devastated by fires and earthquakes. Economic decline, depopulation and internal warfare ensued. Within a century, the highly advanced Mycenaean civilization collapsed.

From about 1100 BC to 800 BC, Greece descended into a “dark age”, only to reemerge in the 8th century BC with the rise of a new urbanized Greek civilization centered in Athens.

Mycenaean Palaces: Centres of Power and Commerce

Mycenaean palaces were ruled by a king, and served in turn by a rigid hierarchical society of warriors, administrative officials, landowners, artisans and slaves. The chair seen in the picture shows the seat of King Minos.

The palaces were protected by massive defensive walls and contained many rooms. The King conducted business in the megaron or throne room. Adjacent rooms included domestic quarters, guardrooms, stores, chariot sheds, and specialized workshops. Sleeping quarters were on the upper floor. People lived in settlements around the citadel.

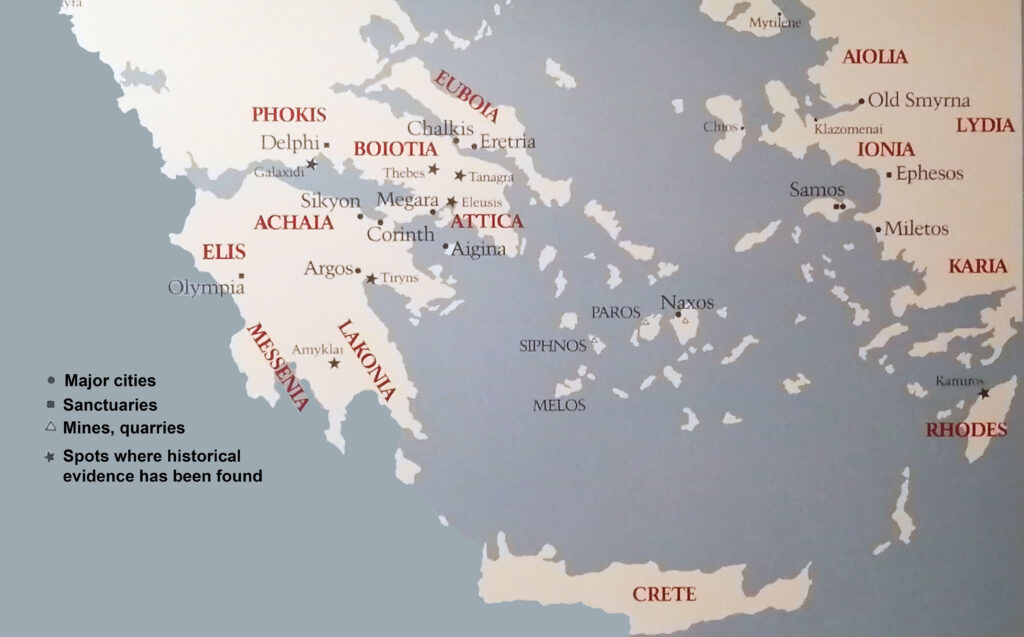

The Mycenaeans controlled a vast commercial shipping network that extended from Italy to Syria and established colonies in Cyprus, Egypt, Miletos and Rhodes. They imported copper, tin, gold, ivory and gemstones. Their exports included weapons, jewellery, olive oil, perfume, wine and wool. Palace officials used Linear B script (an early form of Greek) to keep written records of commercial transactions, inventories, land tenure, and other matters of interest to the state.

The Geometric Period: beginning of the Iron Age 1050-700 BC

After the collapse of the Helladic Civilization and Mycenean rule, the early Greeks lived in small, isolated farming villages with scant overseas trade. They made their tools and weapons from iron as well as bronze.

Revived trade with the East heralded a new era of prosperity. New Greek colonies were established along the coast of Asia, in southern Italy and Sicily. Jewellery, pottery, bronze work and ivory carving became markedly more sophisticated. Literacy was reborn with the development of the Greek alphabet.

Early Greece: 1100-700 BC

After the decline of the Mycenaean palaces, Greece entered into a “Dark Age”. Society fell apart, and 4 out of 5 Mycenean settlements were abandoned. Local war-leaders emerged, constant warfare and local shifts of population occurred. Only a few of the old centres survived these upsets, maintaining scanty contacts with the outside world. Some of those centres were Athens, Crete and Euboia. Some refugees fled to Cyprus and Western Turkey. Half-remembered names and events from the past became the basis of myths, which were preserved in literary works.

The old leaders were regarded as semi-divine heroes, and by 800 BC, shrines and temples were being built in their honor. In those hard times, when iron weapons were coming into use, men looked back to a happier “age of bronze” and a mythical “golden age”. Foreign contacts were resumed in the 8th century BC, bringing new art styles and alphabetic writing from the east.

The Orientalizing Style: about 700-550 BC

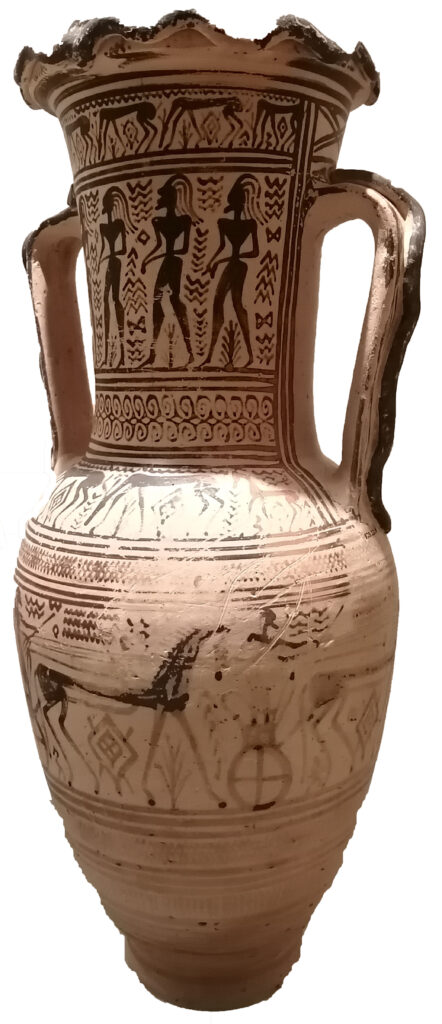

Around 700 BC, new influences from the east profoundly changed Greek art, leading in time to the classical Greek art style. Frienzes of animal figures, both real and imaginary, such as sphinxes, were borrowed from Middle Eastern pictorial art. Imported carved ivories and textiles may have been the chief sources of inspiration. The figures are rather stylized and treated according to set conventions and often appear on a richly patterned background.

Greek Daily Life

Painted vases and terracotta figurines are a valuable record of the past. Through them, the ancient Greeks recorded themselves at work and taking their leisure. Private feasts and drinking parties (symposia) were attended by men only, except for any female entertainers hired for the occasion. The guests were served as they reclined on couches; when the meal was over, the drinking and entertainment began. The wine was usually mixed with water to make it less intoxicating. These symposia were also an opportunity for the intellectual discussions so treasured by the Greeks, particularly the Athenians.

Indoor lighting was provided by burning olive oil in clay or bronze lamps. Stronger light could be obtained from lamps equipped with several wicks and nozzles.

Personal adornment was as popular in antiquity as is today, both for women and men. From prehistoric times on, gold was held in great esteem, and was believed by many to possess magical curing powers. Fine metalworking techniques were perfected in historical times. During teh Archaic and Classical periods (600-31 BC) the emphasis on Greek jewellery styles and techniques was placed on fine, meticulous goldwork. Later, after Alexander the Great’s conquests exposed the Greeks to the vast wealth of the East, their taste changed. During the Hellenistic period (about 323-31 BC) a much richer and opulent look was preferred. Large pieces of gold jewellery, embellished with colorful precious and semiprecious stones and enamels, became fashionable.

Alexander the Great (336-323 BC) and the Hellenistic Age

Alexander the Great came to the throne of Macedonia, the dominant power in Greece in 336 BC, and undertook the Greek conquest of the Persian Empire originally initiated by his father, Philip II. By the time he died in 323 BC, Alexander and his army had defeated the Persian King Darius III, seized most of the Persian territories, and fought their way as far east as the Indus River.

After Alexander’s untimely death due to a fever, his generals agreed to divide responsibility for his empire among themselves. Within a short time, however, they established independent rule over their individual territories. In the Mediterranean region, most of these kingdoms gradually fell under Roman rule during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. In the eastern regions of the empire, a reemergence of native rule provided cultural continuity with the pre-Hellenized past, while retaining the new ideas brought by the Greeks.

As a result of Greek expansion, Alexander and his successors spread Hellenic culture, art and technology throughout the territories they conquered. The coins used by these leaders and subsequent dynasties provide graphic evidence of this influence and of the turbulent politics of the time.

As Alexander expanded his territory through successful invasions of the Persian empire, the need for a uniform large-scale currency was created. Mints at various centres struck coins of similar design – each mint adding its own symbols and monograms to indicate the different issues. These coins continued to be issued after Alexander’s death until his successors gradually began to strike money bearing their own names and titles.

After Alexander’s death in 323 BC, his young half-brother Philip III and his posthumously born son Alexander IV were chosen to inherit the throne under the trusteeship of Alexander’s generals. Philip III’s coinage copied that of his predecessor except that Philip’s name replaced Alexander’s. After Philip was murdered, teh mints again struck coins bearing Alexander the Great’s name – until those generals who had proclaimed themselves kings of their respective territories began to issue their own coinages.

The Hellenistic Age: 323-31 BC

During the three Hellenistic centuries from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC to the final conquest of Greece and the eastern Mediterranean by the Romans in 31 BC, Greek culture, including the arts, flourished in many centres, most of them outside of mainland Greece. Alexandria in Egypt, Pergamon, Didyma, Miletos, and Ephesos in western Asia Minor (now Ephesus, Turkey), the island of Rhodes and many others were now important new capitals and flourishing cities of Hellenistic kingdoms.

Hellenistic art was more diverse and worldly than the idealistic art of the preceding Classical period. It reflected deep interest in, and knowledge of, human nature in all its aspects, both tragic and comic.

Objects of everyday use, some simple and others highly decorative, were made by skilled craftsmen working in such varied materials as glass, faience, alabaster, metal and pottery. Vessels of gold and silver set the fashions for craftsmen working in other materials.

Decorative glass containers, known in Egypt a thousand years earlier, appeared again in the Greek World after 600 BC. The primitive core technique employed was suitable only for small closed containers. By Hellenistic times, large numbers of these were being made in the eastern Mediterranean, and again in Egypt, in shapes mostly copied from Greek-style pottery and metalware. At the same time, open bowls, made by melting glass frit in moulds, came into fashion, these include some ornately decorated varieties.

The Hellenistic period ended with the final conquest of the heartlands of Greece by Rome, which was the result of the Achaean war. The final defeat of the kingdom was at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. At that time, Roman emperor Constantine the Great moved the capital of the Roman Empire to Constantinople (present-day Istanbul).